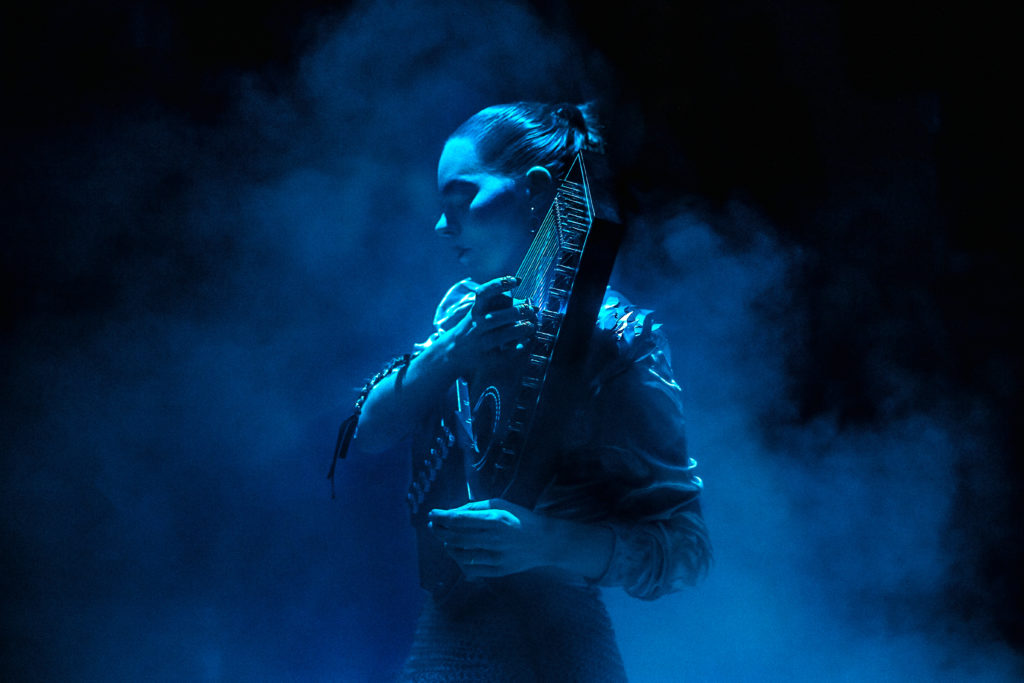

Petra Hermanova is a musician and visual artist based in Berlin. In 2018 Hermanova began working with the autoharp and it has since become the central pillar of her musical practice. Drawing inspiration from medieval drone, doom metal and contemporary textural expressions, as well as Appalachian autoharp music, she creates emotionally driven arrangements accompanied by vocals. In her lyrics, she speaks to the fragility and tenderness of the human condition, religious conceptions of death, and introspective landscapes through narrative and symbolism.

Before your solo music career, you were active in a renowned Czech project called Fiordmoss. What preceded this? What led you to active music-making?

In my family, we listened to a lot of music when I was growing up. The spark to write something was a summer encounter with touring Irish musicians who played some shows in my hometown in Moravia. By September, I’d written my first song, I was fourteen. This is my third rebirth as a musician, with periods in between when I thought that I’d never return to music. Now I’ve come to think of music in my life as a phoenix. It’s this breathtaking creature that I devote myself to fully, and then one day it combusts and turns to ashes in a huge funeral pyre. Then I mourn and wait for the next cycle to begin. So music has always been an all or nothing situation for me, because I’m incapable of not taking it seriously. This Irish friend of mine told me recently that I was deadly serious even back then, around the time I wrote my first song.

Following Fiordmoss’ demise, it seemed as if there was a certain hiatus, between the ending of the band chapter, and your solo venture. How do you recollect this period, and what led you back to the stage and studio?

My first break from music took me to art school, where the band started. The second time around, after it was over, I went into my Švankmajer era. I immersed myself in animation and developed an animation technique, which involved late night scanning sessions and experiments with organic matter. I was doing a lot of visual work for other musicians. In this way I could interact with music without having to be the face of the project, and staying in the background was very healing for me. That was when I started collecting autoharps. For a long time I kept it a secret, so that no one would ask me if I wanted to make music again. And I really didn’t, I was just enjoying being an autoharp nerd, working out different setups, learning. Eventually some friends found out and lured me out of my silence to play a song at their show, write a song for a release, things like that. At the same time, Philipp Hülsenbeck and Tim Roth had just started their label Unguarded, and they asked me to play a concert at an event they were curating in this high-tech brutalist congress centre in Berlin, which reopened for ten days after a decade of closure. It is entirely contaminated with asbestos, I couldn’t say no.

In an interview, you mentioned that you are looking for ways to function in this life without the principle of beauty. How to “imperfect” perfection? How to make it more “humane”? Your music on your solo album could also be called beautiful, but you are drawing from darker topics, like death, grief, mourning…

I feel honoured when people tell me they find my work beautiful. I don’t think I really want to be able to function without beauty, or to create things that are explicitly not beautiful. But I think it is a good exercise to go against our automatic creative processes. Sometimes, the things we see as not beautiful later turn out to be the bearers of a new sense of appreciation. Like growing an extra cone to perceive a new colour. It’s a practice of shifting perception. Grief may be seen as a darker subject but it’s not the opposite of beauty. Most of our change and growth into more beautiful beings comes from intense introspection, which is often triggered by difficult experiences. They bring a perspective that wasn’t there before. When it comes to perfection, it’s important to remember that it’s not a universal thing. So one must abandon the work before it is ruined by being too done, too dead. There’s a scene in El Topo, where we learn that too much perfection is a mistake. It’s a simple thought but implemented as a method, it can be very liberating, especially in the later stages of creation, which tend to take the longest.

Can you talk about the recording process of your album In Death’s Eyes? The album features an interplay of the “heavenly” (organ) and “earthly” (autoharp). It is a spiritual but also human, fragile record.

The songs were written in about six months. It became pretty obvious that they had outgrown the limits of my studio, and that I’d need to record an organ. Philipp came up with Merseburg and found an organist through his connections. Inside the thousand-year-old cathedral sits an incredible 19th-century organ, and Denny Wilke, as we immediately saw, knows the instrument very well. We placed microphones all over the place, inside the organ as well. I wanted to treat it like a living creature, and record the expansion and contraction of the organ’s lung, the creaking and shifting and wheezing. These sounds ended up being the only percussion on the record, and in some places they also tell a part of the story. Watching Denny play these songs was an experience out of this world. After the organ recordings were finished, I recorded my autoharps and vocals in two different churches in Berlin. We also put together a small choir with friends and recorded that in the fourth church on a particularly cold day. It was a real community effort to get some of this done and I am grateful to everyone involved.

What is your relationship with your audience – imaginary and real? When you write your lyrics, is it more about being diaristic, confessional, or reaching out and communicating with your listeners?

Writing lyrics has always been an intense process for me, I react very strongly to words, so I’ll spend a long time before I’m ready to let it go. For this album, I had nine themes in mind that I wanted to write about, so it was about distilling the themes as best as I could into as few words as possible. And the fewer the words, the heavier they become. It’s an obsessive, unnerving process. So there’s no space to think about an audience. On stage it’s a different story. Even though I have only played a handful of shows with this material so far, one of the things that has stood out to me was the atmosphere of deep listening in the audience. I know it’s not always like that because I’ve played a lot of shows before. This is the kind of an audience that makes me a better musician; when I am not alone with the music, and the energy flows in both directions.

How important is visual aesthetic to your work? The album cover art, and the videos have quite a specific atmosphere.

The visual acts as a portal through which one gets to the album. It can also communicate several ideas at once in a fraction of a second, it makes us feel something immediately. This is in stark contrast to the music, which requires your presence and time, even patience. For this record, I’ve enlisted Evelyn Bencicova and Enes Güç to work with me on the artwork, and Odious Rot to take care of the material form of the album as an LP. They’ve all been incredible and their depth and dedication added so many layers to this album. I highly recommend everyone to go discover their work. It was rewarding to see this collaboration expand when Enes then also directed a video for “Black Glass”. But I have to add that the personal aspect of it was what was the most important. With any significant body of music, it can take years to fully understand what we actually did there as musicians, especially when you work so intuitively. Having a direct line to the minds of these artists has given me more vantage points for understanding the context of my work. This ignites new fires.

How do you transfer the intimate nature of your songs to a stage?

I try to make sure that it is the right stage to play my music on. It influences what kind of an audience will come, which is directly related to what I can do on that stage.

What inspires you lately?

Usually it’s the latest addition to the collection of instruments. So right now it’s a harmonium that we just got from a friend. I’m working on a mix, which is kind of a new thing in my life, so I’m enjoying listening to music in a more research-based way. I feel totally overgrown and tabula rasa at the same time.

Interview by Lucia Udvardyova

Photo by Bine Banner